[Listen to an audio reading of this post by the author here!]

“How have you been feeling in this quarantine season?”

“I feel….just ok.”

There are so many emotions that are tied to “ok.”

I knew that there was so much more underneath the surface when I said that. What is it though? I felt confused for weeks. Why was that my answer every time someone asked me how I was doing?

The days of the quarantine then turned to weeks, and the possibility of it becoming months settled in. I observed my community around me grieve the loss of many things: cancelled plans, outings with friends, the many lives that are being taken, the previous sense of what was considered “normal.” I saw people getting frustrated and angry at having to stay home. I observed people breaking social distancing rules in order to hang out with friends that they missed.

And while I saw this happening, I felt a deep sense of anger, although I pushed it down and continued with life.

“Let’s do a check-in. How are you all feeling?”

“I’m not sure. Something about this season reminds me of my childhood.”

I shocked myself when I started unraveling the deeper layers to that statement. The home cooked meals naturally reminded me of when my mom would cook for me every night but this was much deeper than that.

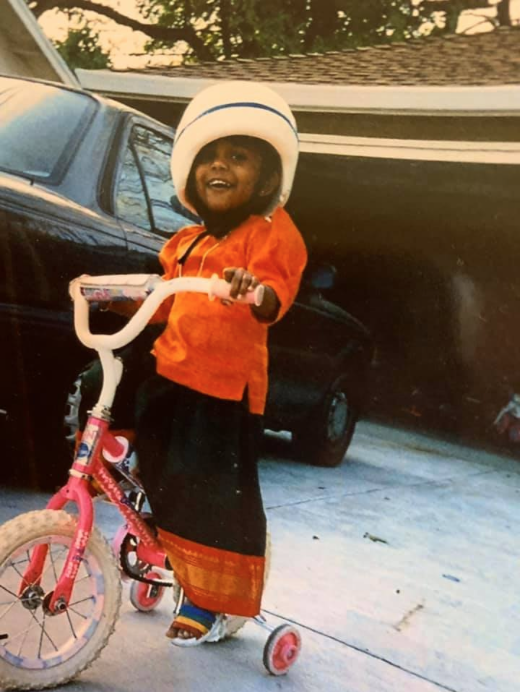

The lack of freedom and agency for me to choose what I wanted to do and who I wanted to be with is how I grew up for the majority of my life:

I wasn’t allowed to go to the library to study.

The first time that I got coffee with a friend was the second semester of my senior year in high school.

When I got my first period, I wasn’t allowed to have sleepovers anymore while there were no restrictions for my older brother.

My parents felt uneasy with me going to dances, so I only went to my senior prom after six hours of begging and pleading with my parents.

If I wanted to hang out with my friends, there were many questions that I had to solve before I would consider asking. What mood are my parents in? Are they happy enough for me to ask them? If I do ask, they’ll be angry at me for a week. Can I afford that right now? At some point, I lost the energy to fight to be with my friends. The decision fatigue was too great, and I decided It was easier to just be home.

This is more than just my experience. Many Indian women are stuck in the house with no agency over their social or personal lives. We are used to being told what we can and cannot do so having the government tell us to stay home doesn’t feel any different.

The mental, physical, and emotional strain that the majority of society now feels due to their seclusion indoors and lack of freedom of choice feels familiar to me.

While the freedom that I was given in college was exciting, it was also overwhelming. I didn’t know my capacity to be around people because I had never been given the opportunity. I didn’t have many friends in high school, and I had no idea how to find friends in college. The weekends gave me an unbearable amount of anxiety because I didn’t want to be around people, and I didn’t know how to say no. I functioned with a fair amount of social anxiety that I still experience today. At some point, I craved going home for the weekend. I used my parents as an excuse for why I couldn’t be around friends but was then sad when I saw my college community become closer because of their weekend hangouts.

I also had to constantly defend my parents. I would hear that my parents were “weird” and “overprotective” for asking that I would call every night from my mostly white friend group my freshman year. I received judgemental stares when I told my Christian community that I go home every weekend, followed with “why are your parents so strict???”

And to be clear, I love my parents and they had no easy feat: to raise two children in a foreign country that only valued them for the highly skilled labor that they could provide. America is scary for immigrants and their families. They did what they could to protect me, and I am thankful for them.

I’ve discovered that growing up the way I did gives me a strange superpower in quarantine: I have a deep sense of gratitude. My capacity to be grateful with the simplest things has helped me more than just survive in this season; I’ve been thriving. I find deep joy in my walks everyday, staring at Eucalyptus trees by the ocean, laughing until my abs hurt with my housemates, reading so much more and engaging my creative self through art. It makes me wonder whether we need “freedom” in every sense to thrive. Maybe the way I was raised actually allows for me to access fulfilment in Jesus that distractions of the “normal” day to day freedoms take me away from.

I also grew up understanding that my actions heavily affect my community and those around me. The hardest decision of my life has been deciding to pursue ministry because of how it would affect my family. I felt like I was wasting my parents’ sacrifice, all that they suffered to come to this country by choosing to work in ministry. Overall, I thought about the implications of my decision on my family more than how my actions affected me.

As I’ve operated most of my life, thinking of my family and community before myself, I find it appalling that people in our society would choose to put their wants before others’ lives. I do not understand why people go crazy when some of their freedoms are temporarily taken away for the collective good. And as a South Asian woman in ministry, I am deeply angered as I think about white pastors teaching about “the importance of community” while simultaneously taking so long to shut down services at their churches. I hold to the truth the women in my life have taught me the most about sacrificial living in community.

These aunties gave up everything–their community, their career, their sense of freedom–-to move to a new country for the opportunity to provide their children with a better life. I think of how their immigration story is simultaneously a story of surviving multiple patriarchies. I think of the Patti Ammas that faithfully wake up before the sun to cover every member of their family in prayer. Why have their voices not been heard when we talk about “bearing our crosses?” Why are those that exemplify communal living the most still silenced in our churches and pulpits?

In the midst of these questions, I do believe that Jesus has something to say to South Asian women. Jesus regularly healed and walked alongside the women who were most marginalized in society. Jesus enters into our houses, and he doesn’t expect us to go to the mountaintop to meet him. He will come to us if we ask him to. When he was in Mary’s house and she honored him, he rebuked the men that belittled her actions. Jesus will listen to the one in the room, or the household, whose voice is the quietest and he’ll exalt them. He will turn cultural dynamics on its head in order for your voice to be heard. He will amplify your voice further than you could ever have done yourself.

I have to believe that he sits with us in our homes as we argue with our parents. He holds the tears that we quietly shed so that our family doesn’t hear. He knows about all the last minute lies you had to tell your friends because you weren’t allowed to leave the house. He understands the different ways that you’ve had to code switch in different situations and the fragmented parts of your identity. He feels the social anxiety that you had, even when no one else saw it. He knows our souls and our hearts better than anyone else could, and he will amplify and honor our voices.

Comments are closed.